Prioritization and Uncertainty

Why does the conversation always come back to prioritization?

Any discussion of ways of working with teams, with organizations, with portfolio leaders… we end up looking for that magic heuristic that can help us “separate the wheat from the chaff”.

And leaders hear this concern all the time, from their teams and peers:

- “I’m confused on the priorities.”

- “We have too many top priorities!”

- “Those might be your priorities, but they’re not mine…”

- “Our priorities keep changing!”

But it makes sense. Because when we talk about priorities, we are recognizing some basic needs across operations:

- A need for focus… for good strategic alignment that helps us coordinate our large efforts

- A need to deal with finite constraints… since there is always “more to do” than time and resources with which we can do it

- A need for speed… to emphasize flow or throughput, by placing limits on the work-in-progress

Solving for these needs requires decisions about priority. And like all decisions, these will drive the allocation of resources. What we’re doing vs. what we’re not going to do. That’s why it can get so heated. And also why we can’t avoid it.

But decisions made in the presence of uncertainty are harder. More complicated. More frustrating to make and to communicate. So we need better approaches, when faced with significant uncertainty when making prioritization decisions.

Prioritization is about taking a set of options or opportunities and sorting them out by importance and urgency. It usually drives the sequence with which you attack the options. Because if it’s the most important and the most urgent, then you probably want to do it next, right?

But you’ll need a way to decide what constitutes importance. That will obviously depend on your context. And even urgency can depend a bit on context, but the key thing there is just to remember to talk about it alongside importance.

The comparison amongst the options will be relative. Relative to each other, which we sometimes refer to as opportunity costs: “I think this thing is important (and urgent) and doing it next won’t starve resources from a better opportunity.”

But how sure are we of this? This is where conversations can get difficult.

Options or opportunities all start out as a twinkle in someone’s eye. They are just a raw and rough idea. We’re not supposed to be sure of anything about it, at this point. Just that it seems like it might have some promise.

Usually, we allow for a refinement of ideas via some kind of “intake” mechanism - a proto-backlog of stuff that we’re still molding into something we can prioritize. But here’s the thing:

- That molding, or refining, of our understanding never really stops. That’s the learning that we are doing all through execution, and which doesn’t end until value is realized.

- That molding, or refining, or learning isn’t free. We spend resources on that. And there is opportunity cost on that. So that choice is part of this “how to make decisions on priorities” conversation.

Is yields questions about prioritization like:

- How should I balance time spent on ideation and refinement vs. pursuing prioritized opportunities?

- When does the amount of time spent refining an idea become too much time?

- When does the importance and urgency of collecting more information (for refining a new idea) get prioritized over the more mature ideas? Or the ones we are already working on?

To think about these, we’ll need to expand our concept of “value” of outcomes and the outputs that get us there (which is what makes an opportunity important and urgent) to include the value of information itself.

If we can expand our (usually economic) model for value to include a concept of the value of information, then we might be able to compare (and prioritize) work-delivering-outputs with work-getting-information. And we know that work-getting-information is usually the cheaper way to reduce uncertainty.

Why should we consider different approaches to prioritization when facing uncertainty?

When uncertainty is low, there is a lower risk involved with committing resources to execute on our opportunities. We’re likely seeing a straight line from the opportunity to some desired outcome, and feeling confident in our ability to get there. We can put a high confidence level in the expected value of the outcome, or even a version that factors in urgency (e.g. cost-of-delay).

When uncertainty is high, then there is a higher risk involved with committing resources to execute on our opportunities. Maybe we talk in terms of “hypotheses” for these opportunities. Hopefully, there is enough psychological safety to admit that we’re “only 40% confident” that this proposed output could yield that desired outcome. We can talk about risk.

“Risk is any uncertainty that matters.” - Dr. David Hillson

When we are able to drive a dialog about (and even quantify) risk, then our ability to prioritize under conditions of uncertainty gets better. For example, a product manager might survey the uncertainty across their opportunities and start to organize them around feasibility risk, usability risk, value risk, and business viability risk. These expose the assumptions that form the foundation of our opinions about importance and urgency.

When we consider making a decision to prioritize “Opportunity X”, it’s a fair question to ask whether we understand X well enough to make the decision now. We may need to compare X against “Opportunity Y” which is in progress, and (at this point) much better understood than X. Our intuition or hunch or conviction in X might be strong, but it’s not going to be a fair fight head-to-head (for resources), when Y has the upper hand on certainty. And remember, decision makers looooove certainty (we all do).

So how can we decide when to green-light a little more information gathering (i.e. discovery, research, or just study) on X?

Here we’ll turn to a concept from Douglas Hubbard’s definition of the Value of Information, from “How to Measure Anything”.

Let’s say that “Opportunity X” was a proposed project that would run a marketing campaign (this is Hubbard’s example). In our over-simplified world here, let’s say that the campaign will either be a complete success or a complete failure (check out the book for more real-world examples).

We draw our focus to the Expected Opportunity Loss, which, for an alternative, is “the cost if we chose that path and it turns out to be wrong.” So we’ll start by stating our confidence that this path of doing the campaign is right (60%). Then we’ll explore the expectations of impact if we’re right (usually this is all that gets discussed in a project review!) and the expectations of impact if we’re wrong (... crickets…). We also cover the alternative of “doing nothing” where the impact here is zero (…sometimes it’s not).

The Expected Opportunity Loss for the alternative where we approve the campaign is:

- EOL if approved: $5M x 40% = $2M

For the alternative where we reject the proposal it is:

- EOL if rejected: $40M x 60% = $24M

So for this decision, the overall Expected Opportunity Loss is the sum of these two, or $26M.

“EOL exists because you are uncertain about the possibility of negative consequences of your decision. If you could reduce the uncertainty, the EOL would be reduced. In regard to making business decisions, that is what a measurement is really for.” - Douglas W. Hubbard, “How To Measure Anything”.

This is our opening to extend our economic model to consider the value of new information (what he is referring to above as “measurement”). Just like we have traditionally approved projects or initiatives when the return on investment (or value of the desired outcomes) exceeds some threshold, we should consider investing in obtaining (or just waiting for) a bit more information to emerge, when the EOL on a decision is above some preset threshold. Essentially, we’d be saying, “We’re not comfortable making this call right now, the stakes are too high.”

Compare this to how you might be handling this situation today. A leader comes in with a proposal to invest $2M to yield $20M (they say) over 3 years. They express 70% confidence in this assertion and have dutifully logged a couple risks. Where is the discussion of the coast if it fails? And the comparison to other opportunities through this lens?

Today’s prioritization approaches usually don’t venture into this area of opportunity losses. Like a rerun of “It’s Always Sunny in the Portfolio Review.”

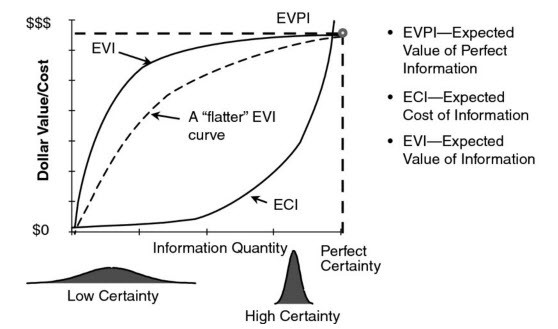

Hubbard defines the Value of New Information as the value of the reduction in EOL it creates:

- Expected Value of New Information (EVI) = EOL(before) - EOL(after)

This gives us something to compare the Cost of Information against, as we mold our ideas from a twinkle to a promising opportunity to a funded project or initiative.

The curves suggest that your bang-for buck is very high when you first start molding.

Or as Hubbard puts it, “If you know almost nothing, almost anything will tell you something.”

It’s only if you continue too far, seeking perfect certainty, that the value diminishes. Our innate desire for certainty can drive us bankrupt, if we let it.

It’s also good to remember that our complex environments - where many moving parts and stakeholder interests meets significant uncertainty - is not a place where we can approach prioritization as an optimization problem. Instead, this is a place for “satisficing”.

“Because real-world optimization, with or without computers, is impossible, the real economic actor is in fact a ‘satisficer’, a person who accepts ‘good enough’ alternatives, not because less is preferred to more, but because there is no alternative.” - Herbert A. Simon, “The Sciences of the Artificial”

So the purpose of prioritization is:

- To communicate importance (and urgency) across the organization

- To “satisfice” in the presence of resource constraints

- To create an environment in which teams can thrive (i.e. with managed WIP)

What form should a prioritization exercise produce? What is the right context and conditions?

- An item is prioritized relative to others in a set. Start by identifying the set. Is it a backlog? A portfolio? A set of businesses? A set of opportunities? Can you set constraints on its size?

- The set should be time-bound. Since our concepts of importance and urgency are relative to time, make the set be time-bound (e.g. opportunities for a specific quarter, or for a fiscal year).

- The decision-maker for the prioritization should be at the right level in the organization. They should be accountable for the results and the risks for the set as a whole. If I’m advocating for one opportunity over the others, and I don’t have any incentives for the success of the others (only mine, as champion), I’m not the right person to prioritize it.

- A prioritized set of items, bounded by time, is the concept of a timebox. Use it to stabilize your prioritization choices to protect the teams from debilitating churn. Large efforts cross-cutting departments need stable timeboxes over longer durations (e.g. stable for 6 months) than small efforts done by teams (e,g, plans for a month or a sprint).

Priorities are decisions, and it’s okay if they need to change (they will, or at least should, occasionally. That’s what a pivot is…)

“Have strong opinions, loosely held.” - Jeff Bezos

But hold them long enough to protect the teams that are executing. Pursue the new information, when the value is there, but when the information leads to changes in priorities, drive those changes to be synchronized to timeboxes, to manage the impact of the changes. Not in an email the next Monday morning.

So as Barry O’Reilly has said, what we need is a “systematic approach to managing the risk of planned work, by gathering information to reduce uncertainty.” Here’s an idea of a modified Eisenhower Matrix that could help shift the prioritization focus to inclusion in a set (e.g. timebox) and also make the uncertainty more visible. This assumes that there is enough uncertainty floating around to warrant describing the opportunities as “hypotheses”.

Overlay a timebox and a resource-constraint “cut-line” on the familiar Eisenhower matrix. Within each quadrant (or set), shift items left or right based on their uncertainty, relative to the others in the quadrant. Look at the value of information to shift items slightly leftward, over the next quarter. Make confidence levels visible to support EOL-based analysis to justify discovery, research, or some deeper study of external conditions. The color codes could suggest these assessments: Is the hypothesis ready for planning (green)? Does the EOL warrant some discovery first (yellow)? Or is it still a twinkle, but with strong agreement that it is a very important and urgent twinkle (clear)?

The active hypotheses could each get a deep dive into their assumptions and risks. You can’t manage what you can’t see, and this could help shift the management focus to better approaches, given the presence of uncertainty.

Would this be a better approach? Not sure yet, still need to try it out. But it might be an effective way to cut prioritization down to what’s essential:

- Communicating strategy - what’s in, what’s out

- Aligning the focus - what’s now, what’s next

- Decisions to help allocate resources - finite sized quadrants

- Acknowledging uncertainty - reducing uncertainty has value, too

Can we avoid prioritization altogether? No, but we can try to minimize the effort we spend on it. We can aim to shift focus and energy from prioritization exercises to learning exercises, where learning truly encompasses both the forming of ideas and the execution of opportunities.

Prioritization under conditions of uncertainty should feel different. It needs a risk-mindset. We should be comfortable talking about when we need to “buy information” and how to effectively purchase it. It recognizes that we will be managing bets: which bet is best? When do they “hit”? How big or small? This is what we will ultimately be prioritizing. And when we can make them small, that naturally leads to agility and adaptability - exactly what we need.

Prioritization is “focus management” for the organization, which is a communication job. Good communication needs common language and shared understanding of context. Make the uncertainty more visible, such that when needs change (and then opportunities change in expected value), you can steer resources, to drive learning, to reduce risk profiles.

And that kinda sounds like a foreign language, doesn’t it?

.png)

.png)